HOW TO GET TO LVIV

I travelled to Lviv from Krakow, so I decided to take an overnight train departing at 21:02 from Kraków Główny railway station. The journey takes about 8h, so I booked a double compartment with beds to spend the night travelling and be ready to explore Lviv early the next day. This allowed me to save almost an entire day travelling that I used visiting the amazing sites of Lviv!

It isn’t easy to buy tickets online for international trains departing from Poland. In most cases, these are only sold directly at the train station. Since I didn’t want to risk waiting to buy the tickets once I arrived in Poland only to discover they were sold out, I used the services of Polrail to buy my tickets.

Polrail is a railway travel agency based in Poland who can help you travel by train anywhere in Europe. They bought my tickets from Krakow to Lviv and had them ready for me at a pickup office located just in front of the train station. Their services and communication were just perfect, so I highly recommend it if you’d like to buy your tickets in advance and online instead of buying them at the station.

The train from Krakow to Lviv was quite old, and I was quite unlucky as electricity was off in the entire wagon. Tickets include bed linen, and although the beds were quite small, it was comfortable enough to get some sleep during the journey. Immigration was pretty straight forward; towards the end of the night, first a Polish inspector came to check our passports, and only a few minutes later a young Ukrainian inspector arrived. She checked my passport in detail, looking at the picture and my face multiple times to ensure that I was the same person. She asked where in Ukraine I was going and for how much time, and quickly stamped my passport.

HISTORY OF LVIV

Lviv was founded in 1256 when King Daniel of Galicia (a historical region in southeastern Poland and western Ukraine) established and named the city in honour of his son Lev. After the destruction caused by Tartar invaders, Lev himself rebuilt the city in 1270 and chose Lviv as the capital of Galicia-Volhynia.

In 1349, the Polish King Kazimierz III occupied the city and ordered to reconstruct it following the typical European plan with a central square surrounded by living quarters and fortifications around the city.

Lviv soon became a major trade centre, with people from all over Europe moving there. Due to this multiculturalism, multiple churches of all rites, as well as synagogues, were built in the city, many of which can still be visited today.

After the first partition of Poland in 1772, Lviv became the capital of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, a region of the Astro-Hungarian Empire. During this period, the city saw a Germanization, with its name getting changed to Lemberg and German becoming the official language, even though Polish and Ukrainian were still widely used.

When the Habsburg Empire fell at the end of World War I, the region was divided between Poland and Ukraine, with Lviv being attached to the Polish Republic. This brought the Polonization of the city, know called Lwow, and caused a huge decline of the rights of the Ukrainian minority of Lviv.

During World War II, in spite of the German invasion of Poland, the region of Galicia where Lviv is located was occupied by the Red Army, along with the rest of today’s Ukraine. The Germans broke their pact with Russia in 1941 and invaded the Ukrainian SSR, capturing Lviv on June and exterminating the population of over 1.5 million Jews that lived in the region.

When the Red Army liberated Galicia in 1944, new borders were defined and Lviv became part of Ukraine. In 1944, a transfer of Poles of Ukraine and Ukrainians of Poland to their respective countries saw the displacement of over 1.5 million people. What once was one of the main Polish cities lost pretty much its entire Polish population, the Polish language and part of its culture.

Today, Lviv is one of the most nationalists regions of Ukraine, with the big majority of its population speaking Ukrainian and supporting the European nature of the city, contrary to the Russian speaking regions on eastern Ukraine.

WHAT TO SEE IN LVIV: DAY 1

After travelling from Krakow overnight, I left my luggage in my rented apartment early in the morning and started heading towards the old town to explore all the historic sites of Lviv.

I walked from Akademika Hnatyuka Street until I reached an open square where the monument to Taras Shevchenko is located. It was erected in 1992 honour of the most famous Ukrainian poet, who is depicted next to a decorative stele that represents the national revival of Ukraine.

Right on the other side of the square, one of the most prominent buildings is the Museum of Ethnography and Arts and Crafts, with a collection of traditional Ukrainian folk and decorative art.

Most of the old town is constructed around Rynok Square, also known as the Market Square, so that’s the best place to start your visit.

This rectangular square, with a size of 142 to 129 meters, is without a doubt the heart of the city since it was constructed at the end fo the 13th century. It was originally designed in a Gothic style, but after a fire in 1527, the entire city was rebuilt in a Renaissance style.

But the truth is that the houses around the square, 44 in total, are built in different architectural styles, from Renaissance all the way Modernist. You will also find four fountains that represent Greek mythological figures: Neptune, Adonis, Amphitrite and Diana. At the centre stands the Town Hall with its viewing tower. The square was declared a Unesco World Heritage site in 1998, along with the entire historic city centre.

As soon as I reached the square, it reminded me of Poland. I had just come from Krakow, so the comparisons were unavoidable! It was evident that Lviv used to belong to Poland, as it doesn’t represent the open squares that can be found in most ex-Soviet countries, including in the capital city of Ukraine, Kyiv.

The most prominent building of the square, located right in the centre, is the City Hall. It was constructed in the Viennese Classicist style between 1827 and 1835 at the place of an older Renaissance tower that had tumbled down.

Today, you can climb to the observation ground of the tower, from where you can enjoy an amazing view of the city from a height of 65 meters. Here’s where I picked up the Lviv City Card, and since the visit is included with it, I decided to climb to the very top, which wasn’t that easy. Without the card, it has an entrance fee of 20 UAH (approx. €0.80), but the views are very worth it.

There are chimes placed on the City Hall Tower which create the unique acoustic aura of the city. The medieval tradition of playing the “City Melody” by a trumpeter daily at noon was renewed in 2011. Lviv City Hall remains the headquarters of the local government: here, the city mayor works and 64 municipal deputies sit their sessions.

On one of the corners of the square, you can visit the Latin Cathedral, one of the most relevant monuments of Gothic architecture in Ukraine. Its origin dates back to 1370, and the consecration took place in the year 1481.

The most valuable relics of the Basilica are the remains of people associated with the Archdiocese of Lviv. The main altar depicts the image of Mary Mother of Grace decorated with the Golden Rose by John Paul II in 2001, and the Golden Rosary donated by Pope Benedict XVI.

On the right side of the Latin Cathedral hides the Boim Chapel, built by the Boim family in a cemetery next to the church that no longer exists. They were a very affluent family that came to Lviv from the Kingdom of Hungary.

The external decoration mixes multiple styles, from Dutch ornamental decorations to Polish and German motifs. It was designed by Andrzej Bemer based on Sigmund’s Chapel inside Wawel Cathedral in Krakow.

Just at the entrance of the Market Square you will find the Apostles Peter and Paul Garrison Church, also known as the Jesuit Church.

The construction of the first Baroque building began in 1610 under the supervision of Jacomo Briani, an Italian architect who used as an example the Il Jesu Church of Rome. There are gravestones of the great military leaders Stanislaw Jablonowski and Dzierduszycki’s family, as well as the chapel of Maria Consolatrix afflictorum (1630). The Altar of Crucifixion is especially valuable.

From 1946 until 2011, the church was used as a book depository. The church was sanctified on December 6, 2011 on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

If you continue walking, shortly you will reach the Church of Transfiguration. It was originally built in 1731 as a Roman Catholic church following the French classicism but with a Baroque interior. In 1783, it was transformed into a library of the Lviv University and completely destroyed in 1848 by the Austrians.

The church was rebuilt using the original design as a Greek Catholic Church and was reconsecrated in 1906 as the Greek Catholic Church of the Transfiguration of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

Entering a small arch passage almost hidden between the buildings you will reach one of the most charming courtyards of Lviv, right next to the Armenian Cathedral of Lviv.

The original church was founded in 1370 by an Armenian merchant inspired in the Cathedral of Ani, the ancient capital of Armenia. It was severely damaged by a fire in 1572, and a stone belfry was constructed in 1571.

The cathedral belonged to the Armenian Catholic archdiocese of Lviv until 1945, when the Soviets killed its administrator, shut down the church and expelled most Polish Armenians from the city. After the fall of the Soviet Union, some Armenian families returned to Lviv and re-established the Parish. Today, it is administered by the Armenian Apostolic Church.

When I was checking the places included in my Lviv City Card during lunch, I notice that I could also visit the Glass Museum, located right in the Market Square, so that was my next stop. Without the card, it has an entrance fee of 20 UAH (approx. €0.80).

The museum, the only glass museum that you can find in Ukraine, has an exhibition of pieces created during the International Blown Glass Symposiums in Lviv.

The museum itself is quite small, but they offer a few audioguide that you can listen to directly from your phone if you like to visit all the exhibits in more detail. Since my time was limited, I just walked around the glass exhibitions, which I found was enough to get a general idea of the glasswork.

Also not originally on my plans but included in the Lviv Card was the Palazzo Bandinelli. Built at the end of the 16th century in Renaissance style, it replaced an old gothic stone house and was sponsored by the merchant/pharmacist Jarosz Wedelski.

In the early 17th century, the Italian merchant Roberto Bandinelli bought the house. In 1629, a regular post office was set up in the building, so that Lviv citizens were able to send and receive letters from all over Europe. The house preserved the Renaissance style, whilst the ground floor interiors were kept in Gothic style.

In the 1920s, the reconstruction of the building took place, and only in 2005, the Lviv History Museum exposition was opened here. At present, the ground floor houses the Post Museum.

I walked towards the north side of the Market Square until I reached St. Eucharist Church, better known as the Dominican Church.

It was built between 1748-1764 and designed by the military engineer, artillery general Jan de Vitte in the late Baroque style on the site of the former church of Sts Peter and Paul.

From the 16th century, the church resembled a Gothic cathedral. The façade sculptures were made by Sebastian Fesinger. Under the dome, there are 18 wooded sculptures of saints. The interior preserves alabaster gravestones of the 16th century, a gravestone from 1816 made by the famous Danish sculptor B. Thorvaldsen.

Just behind the Dominican Church I also recommend stopping by the Book Market, where you can find mainly old books, most of them second-hand, as well as records.

After having visited most of the highlights of the old town, I headed back to Market Square. Waiting right next to the City Hall was the Lviv sightseeing train.

With a departure every 30 minutes, it visits some of the most important sights of Lviv in one hour, including commentary in multiple languages. Since it was included in the Lviv Card, I decided to take it to get a better understanding of the history of Lviv. Without the card, it has a cost of 110 UAH (approx. €4)

It passed not only by the main monuments of the old town, but also some very interesting sites that I would visit in more detail during my second day in Lviv, including the Opera House and the Pototski Palace.

The commentary was a bit monotonous and extremely detailed for those not familiar with Ukrainian history. I may not have taken this train if it wasn’t included in the Lviv Card, but it was something nice to do after a long day exploring the city by foot.

I decided to finish the day with an attraction that wasn’t as historical as all the places that I had visited during the day. After ordering an Uber, I headed to the Beer Cultural Experience Centre Lvivarnya.

This brewery, one of the most famous in Ukraine, has been making beer since the 14th century, and the exhibition in the museum explains the different processes of the drink and the overall history of beer in Lviv. The museum has an entrance fee of 60 (Free with Lviv City Card)

At the end of the visit, you can enjoy a bar with an incredibly modern design where you can order a beer tasting and get some snacks. A beer tasting of 4 different beers cost only 35, so definitely recommend it!

DAY 2

During my second day in Lviv, I decided to explore the area that surrounds the old town, as well as some of the points of interest that I passed by the previous day during the sightseeing train ride that was included with the Lviv City Card.

One of the places that caught my attention was the Potocki Palace, so that’s where I headed first. Built for Count Alfred Potocki, the vicegerent of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, it was built in 1890. In 1919, the plane of the American pilot E. Graves crashed onto the palace during the demonstration flights over Lviv. Repair and restoration works of the building ended in 1931.

Nowadays, it houses an exposition of European art of the 14th-18th centuries in its halls, as well as artistic expositions. Since 2001, the palace became one of the buildings of the Lviv National Art Gallery.

On the way back to the old town, I stopped by the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv with the words in Latin «Patriae decori civibus educandis» («Educated citizens are the glory of the Homeland”) written on its façace.

It is the oldest university in Ukraine, founded in 1661 by the Polish King John II Casimir. The university went through multiple transformations during the centuries due to the political complexity of the region, but the institution as we know it today was established in 1940.

Right in front of the university you will find the Ivan Franko Park, a perfect place for a stroll. The entrance of the park has an imposing statue of Ivan Franko, famous for being one of the first poets to write in the Ukrainian language. His work, along with that of Taras Shevchenko, had a huge impact in the political thought and national identity of Ukraine.

One of the most emblematic buildings of Lviv and Ukraine in general is the Lviv Opera. It even appears in the notes of 20 UAH.

The Opera was finished in 1900 when Lviv was the capital of Galicia, an autonomous region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The building, built in a Renaissance and Baroque style, presents a richly decorated facade with Corinthian columns, statues, reliefs and balustrades.

A very interesting fact about the building is that the Opera was built right on top of the River Poltva. At the beginning of the 20th century, the river was covered to gain some building terrain and was diverted to flow beneath one of the central streets of Lviv, Freedom Avenue, as well as the Opera theatre.

I continued walking north-east from the opera until I reached the Church and Monastery of the Benedictine Nuns. This Benedictine complex is an ancient spiritual monument and a pearl of the Renaissance architecture of the city of Lviv. The author of the architectural enable of the church and the monastery was the Italian architect Paolo Romano.

The monastery was founded in 1595 for the Benedictine nuns which in 1939 were forced to abandon the monastery and leave to Poland. After the legalisation of the Ukranian Greek Catholic Church, the government of that time returned the monastery to the status of a sacred edifice.

Hidden in an alleyway between Staryi Rynok Square and Knyazya Leva Street you will find one of the most picturesque places in Lviv, the Yard of Lost Toys.

This courtyard has a display of old toys that were left behind. The toys were kept in a small courtyard under a small roof in the hopes that its owner came to collect them, which generally didn’t happen, creating a small collection of abandoned toys that kept growing with the years. Visitors are welcome to bring with them any toy that they like, although unfortunately most of them are in a pretty bad state due to the inclement weather.

A few metres ahead you will find the Temple of John the Baptist. The possible dates of the temple’s construction are 1201, 1232 and 1250. According to the most popular version, the template was built by prince Lev for his wife Konstantsia, the daughter of Hungarian King Bela IV.

The biggest renovation of the template in the Neo-Romanesque style was in 1889. In the 1980s, the template received its primary look when the Neo-Romanesque façade was replaced. Nowadays, it houses the museum of Lviv ancient monuments, a branch of the Lviv National Art Gallery. It is also the place for liturgies by the Greek Catholic Church.

From the Temple of John the Baptist, I originally planned to climb to the Lviv High Castle, as I had read that it offers some amazing views of Lviv. Since I had already enjoyed great views of the Old Town from the tower of the Town Hall, I decided to head back to the city centre and get tram number 2 to the Lychakiv Cemetery. Transportation was included with my Lviv Card, but if you don’t have one, the fare is only 5 UAH (approx. €0.20).

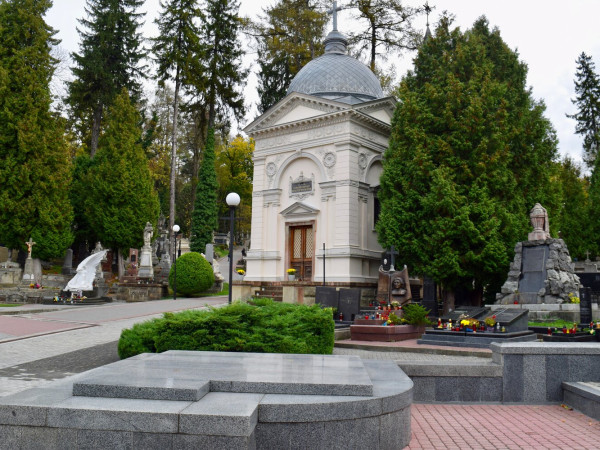

The Lychakiv Cemetery is one of the most famous sites in Lviv, officially opened in 1786. The necropolis covers an area of 42 hectares and comprises 300,000 graves, 5,000 tombs, over 500 sculptures and 23 family chapels in 86 numbered sections. The oldest tombstone is dated 1675. The Lychakiv Cemetery has been under the protection of the Lviv City Council as a Historical and Cultural Reserve since 1990.

Some of the most famous tombs include those of Ivan Franko (a Ukranian poet), Tadeusz Jordan-Rozwadowski (a Polish military leader and founder of modern Poland), Solomiya Krushelnytska (a Ukranian opera singer), Stanislav Ludkevych and Igor Bilozir (famous Ukranian composers), among many other local personalities.

The area of the cemetery is huge, but at the entrance you will find an itinerary that you can follow to see some of the most impressive tombstones. Although visiting a cemetery may not be a typical tourist attraction, some of the statues and mausoleums are truly impressive!

I fell in love with Lviv since the moment I set foot in the Old Town. Before visiting Ukraine, I was expecting it to be the typical ex-Soviet country with dull-looking architecture, but Lviv is clearly an exception. Due to its historical ties with Poland, Lviv has one of the most charming Old Towns that you’ll find in Eastern Europe!

If you’re looking for getaway in a beautiful city off the beaten track, I can’t recommend Lviv enough!